By Alex Mifsud, CEO & Co-Founder, Weavr

How the next airline failure will test whether the travel industry has truly fixed its structural payment risks – or just pushed liability further down the chain.

When Thomas Cook Group collapsed in 2019, it sent more than 150,000 travellers home on emergency repatriation flights and cost the UK government over £420 million in ATOL refunds and operations. It also exposed a deeper flaw in the travel economy: the payments infrastructure that connects airlines, intermediaries, and consumers was never built to absorb supplier failure.

Five years on, the industry looks different – but the underlying risks haven’t vanished. Airlines still fail, intermediaries still carry liability, and acquirers still cap their exposure. What changed is how those risks are managed – through data, technology, and sometimes illusion. We explored the original chain of risk in The Next Airline Collapse Doesn’t Have to Bankrupt Intermediaries. This piece looks at what has – and hasn’t – changed since.

After the storm: what really changed

Since 2019, acquirers and travel platforms have spent millions re-engineering their risk posture. Regulators reviewed insolvency protections, card schemes reinforced consumer guarantees, and platforms introduced virtual cards and trust accounts to limit exposure.

Those steps helped. But as Deloitte observed in its Future of Travel Payments 2024 report, “even where risk controls have improved, fragmented data continues to undermine real resilience in travel value chains.” In other words, the pipes look new, but the plumbing still leaks.

Airline failures haven’t disappeared: Flybe collapsed twice (2020 and 2023), WOW Air, Avianca Brazil and Go First all folded in recent years, and the most recent Play Airlines ceased operations just weeks ago. Each one triggered refund waves and chargeback claims that rippled through intermediaries and their acquirers. The UK Civil Aviation Authority noted that airlines continue to face “significant practical difficulties in providing timely refunds” after large-scale cancellations or insolvency.

The pattern endures, and some cures may be unwelcome. In the UK, the CAA’s ATOL reform process is actively consulting on segregation of customer monies via trust or escrow accounts. In the EU, the ongoing revision of the Package Travel Directive focuses on stronger insolvency protection (e.g. insurance, bonding, or trust-style arrangements), but does not mandate trust/escrow EU-wide. This kind of solution ties up working capital, and increase operational and compliance costs in an industry with such thin margins that can scarcely afford more cost: in submissions to the CAA, industry participants flagged risk of exit, reduced competition and higher consumer costs.

What then, is to be done?

Virtual cards matter – but only when the data does too

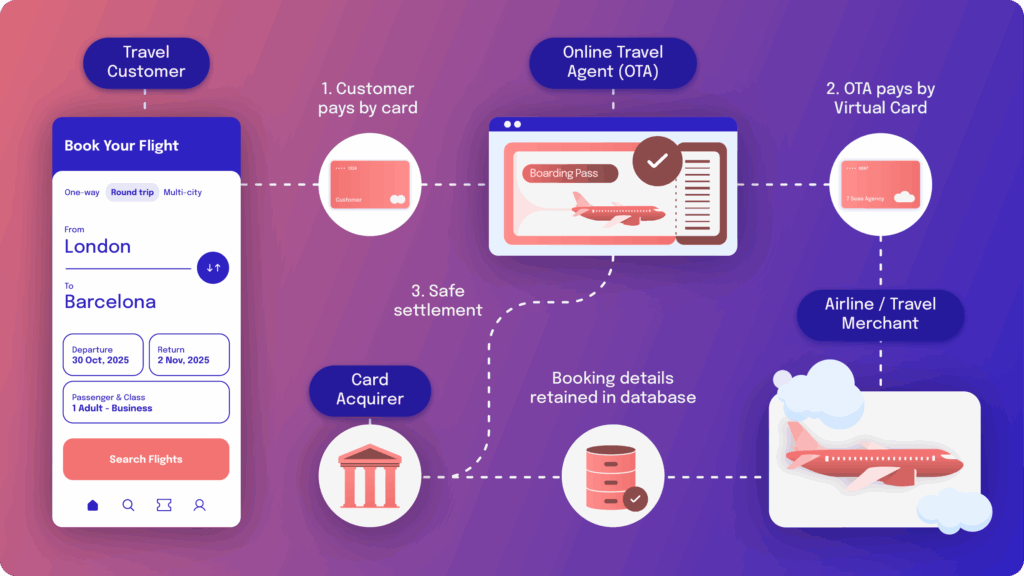

For travel-tech platforms, issuing virtual cards to pay airlines or hotels has become standard practice. Each booking generates a dedicated card; the card-scheme guarantee adds a safety net; reconciliation improves. For many product teams, that feels like structural protection.

But the comfort is misleading. A virtual card alone doesn’t prove what it paid for. If an airline collapses and thousands of chargebacks hit, acquirers demand booking-level evidence: lead passenger names, flight numbers, timestamps, fulfilment records. Without that metadata, the scheme’s protection can falter.

ManyOTAs and aggregators still store booking and payment data in separate systems. So when the need to file a mass of chargeback claims against the defunct airline, operational teams scramble to map card transactions to bookings – an exercise that is manual, slow, and often incomplete. In the Thomas Cook collapse, some intermediaries spent months reconciling spreadsheets before they could reclaim funds, and many were challenged by the airline’s merchant acquirer on the grounds of incomplete or incorrect information. It isn’t a technology problem as much as a design problem: the payment rails don’t speak the booking rails fluently enough.

Acquirers are the next domino

Acquirers live in the shadow of this same opacity. They underwrite travel merchants but can’t always see what sits beneath the transaction volume: which airline, which route, which fulfilment risk. Their exposure is capped by policy, not by insight.

As one payments executive told the Financial Times after the Thomas Cook collapse, “Airline and travel exposure is a known high-risk class. Acquirers mitigate, but they can’t model it with confidence because data stops at the merchant.”

That’s why acquirers who service OTAs and consolidators typically limit travel volumes to a small percentage of their total book, hold rolling reserves, or buy costly insurance against supplier default. It’s defensive capital – money that could be deployed for growth if they simply had visibility into the end-to-end transaction chain.

The Paysafe Travelling Light white paper describes how acquirers “require cash collateral (hold-backs) from travel merchants, big enough that they can, and do, collapse as a direct result.” The irony is that both sides – platforms and acquirers – possess half the picture. The OTA knows which flight a payment funds; the acquirer knows when the payment clears. What’s missing is the bridge that turns those halves into a coherent model of exposure.

The missing architecture

The structural answer isn’t new payment methods or some innovative financial instrument – it’s joined-up infrastructure. When acquiring and issuing coexist inside a single data framework, every transaction can be tracked from booking to settlement.

Imagine this sequence:

- A traveller books a flight through a travel-tech platform.

- The platform collects payment (acquiring).

- At the same moment, the platform issues a virtual card to pay the airline (issuing).

- Both legs are linked by one booking ID and metadata payload.

If that airline later fails, the acquirer and issuer can reconcile every chargeback instantly, with verified booking data and funds traceability. The risk isn’t shifted – it’s controlled. Acquirers gain real-time visibility into exposure; platforms gain an auditable flow of funds and automatic reconciliation. The card scheme guarantee can then do what it was designed to do, all the way from the airline’s bank to the travel agent and finally on to the consumer – all without any insurer stepping in to make good for either the travel agent or the consumer.

This architecture already exists in fragments: some large payment providers have built dual-stack capabilities for enterprise merchants, but mid-market travel platforms have lacked access until embedded-finance providers made it modular. It’s the technical equivalent of putting acquiring and issuing under one roof, with data as the shared ledger.

Why the old model still hurts margins

Without this connection, acquirers remain reluctant to grow their travel portfolios, leaving billions in potential volume untapped. For intermediaries, the cost of that caution is higher MDR (merchant discount rate) fees, stricter terms, and fewer acquiring options. Paysafe’s report notes that travel-sector hold-backs and collateral requirements often “wipe out the profit margin of the very merchants they are designed to protect.”

So long as data and flows stay siloed, those costs are treated as inevitable. They’re not. They’re artefacts of design decisions made before the concept of “platform as payments orchestrator” existed.

Embedded finance – the plumbing that fixes the leak

Embedded finance is not a buzzword here; it’s a potential enabler of this joined-up architecture. It lets a travel-tech platform or acquirer integrate both pay-in and pay-out capabilities, preserving booking-level data across every step. You gain control over how and when funds move – and the intelligence to intervene before risk materialises.

Platforms like Weavr enable precisely this kind of orchestration – embedding issuing and acquiring logic through compliant APIs that live inside your product rather than outside it. That means less capital locked in reserves, fewer manual reconciliations, and a payment stack built for resilience rather than reaction.

When the next airline collapses – and one eventually will – the question isn’t whether customers will be refunded. It’s whether your platform or acquirer will need to absorb the shock. Those who’ve joined their financial plumbing end-to-end won’t just survive; they’ll keep trading while everyone else pauses to count the losses.

Operate in the business of travel space? If you’d like to discuss who Weavr can help turn the risk into an opportunity, talk to one of our experts or learn more about our solution here.

Explore the wider implications

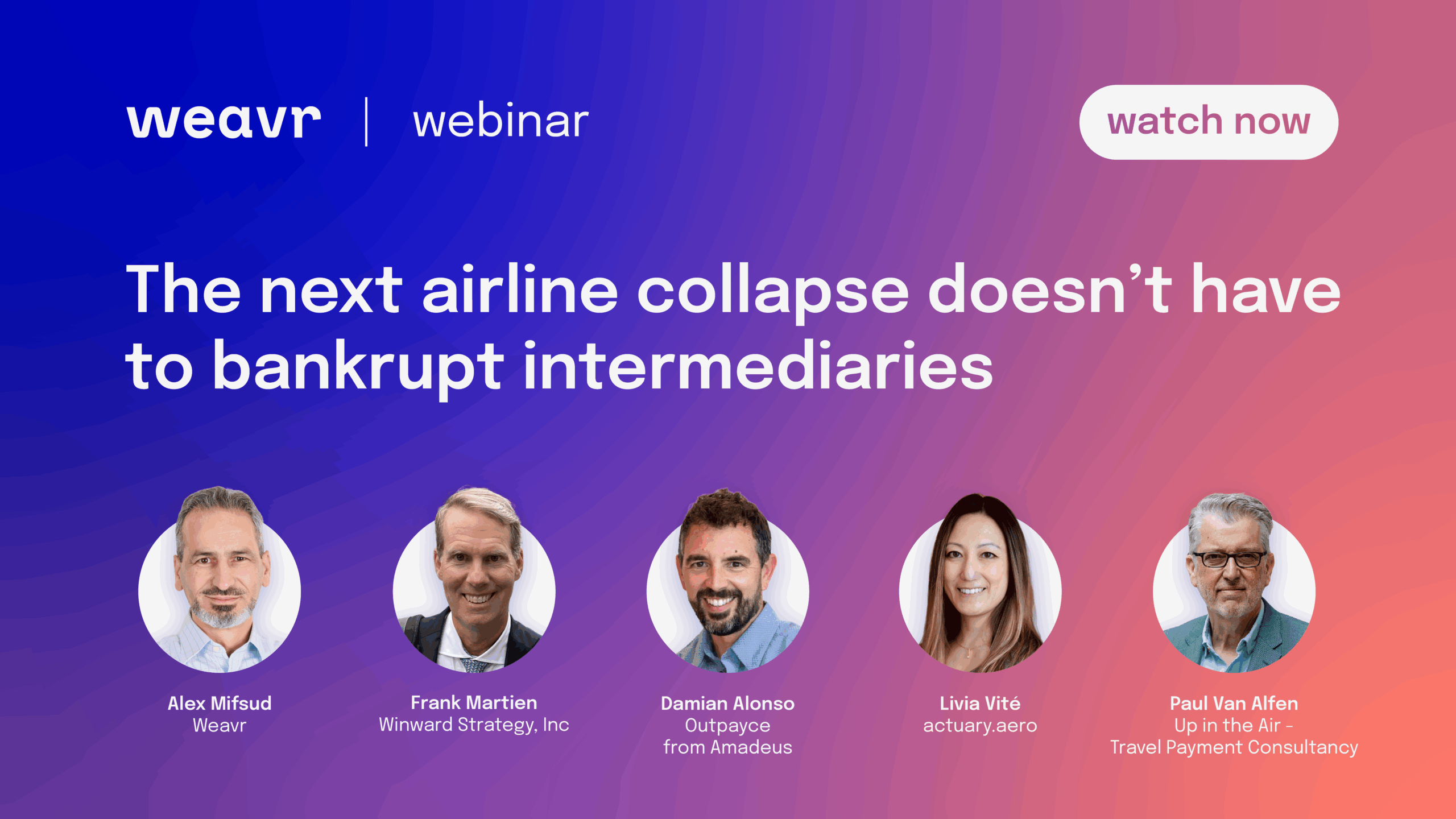

You may find it helpful to read the companion piece that sets out the broader context around why the next major airline collapse does not have to place intermediaries at risk. It examines the systemic vulnerabilities across the ecosystem and outlines the commercial realities that shape current exposure.

You may also wish to watch our senior level webinar on the topic, featuring Livia Vité of actuary.aero, Damian Alonso of Outpayce at Amadeus, Paul van Alfen, and Frank Martien. Together, these resources offer a fuller view of the pressures facing intermediaries today and the practical frameworks that could support greater resilience across the industry.